What you need to know about mRNA vaccines in light of RFK’s claims

The US health secretary is cutting funding for mRNA vaccines because he claims they are less effective than other types – but that is not what the evidence shows

By Michael Le Page

6 August 2025

Robert F Kennedy Jr, the head the US health department

ZUMA Press, Inc./Alamy

The US health secretary claimed mRNA vaccines are ineffective against respiratory diseases, while announcing he was cutting half a billion dollars in funding for mRNA vaccine development. But this goes against the scientific evidence we have, which shows many mRNA vaccines work as well as – or better than – other types of vaccine. Here is what you need to know to assess these claims.

In announcing the cuts, the head of the US Department of Health and Human Services, Robert F Kennedy Jr, claimed “these vaccines fail to protect effectively against upper respiratory infections like COVID and flu”. Kennedy said the agency would shift funding “toward safer, broader vaccine platforms that remain effective even as viruses mutate”.

Read more

Vagus nerve stimulation receives US approval to treat arthritis

Advertisement

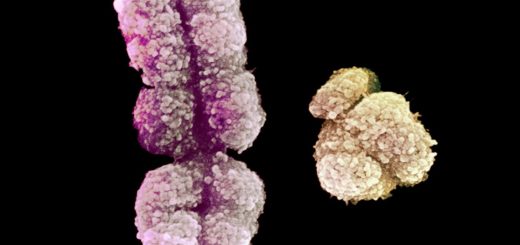

There is now a wide range of vaccine types: live viruses, killed viruses, genetically engineered viral shells, single viral proteins and mRNAs coding for viral proteins. The effectiveness of all of these kinds of vaccines often has a lot more to do with the nature of the virus being targeted than the vaccine itself.

For instance, the MMR vaccine can be 100 per cent effective at preventing measles outbreaks if more than about 90 per cent of a population is vaccinated. But the measles virus is an easy target because it does not change much and it takes a convoluted route deep inside the body, meaning there are plenty of opportunities for the immune system to intercept it before people develop symptoms or become infectious.

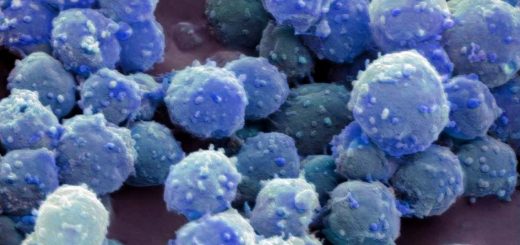

In contrast, the respiratory viruses that cause colds and flus first infect the cells lining the nose and throat. It is hard to generate high levels of effective antibodies in these membranes, so it is much more difficult to prevent infections and onward transmission than with measles.